Why "invisible" illness?

- arielaaviva

- Feb 10, 2018

- 7 min read

How the choice to disclose your condition can be both a blessing and a curse.

I recently had an interesting experience. Every few months, I get a really bad episode of horrible symptoms, probably some kind of dysautonomia. I'm not sure if it's a mast cell reaction or my vagus nerve getting irritated. Regardless, I had this happen on a Monday. Usually it happens on a weekend or vacation, so I can rest up the next day and recover. Not this time; I had to bounce right back and go to work at 7:30 the next morning. It didn't feel great. Usually I feel much better the next day but, possibly due to not resting when needed, I continued to have pretty bad symptoms and actually had to take an Imodium just to be able to stay in the classroom long enough to teach. It was a very rough day.

As soon as I got home, I was pretty beat. I had things I had to get done for the next day, though, so I pushed through. By Wednesday morning, I had a horrible migraine, plus a slew of other symptoms. This continued all week until Friday, when my migraine was a bit better, but I had clearly come down with a bad cold.

The point of this story is actually not to complain about a bad week. It's because of two startling observations I made during this time.

The first observation was that, although I probably felt sickest of anyone at my job, I was the one who didn't take any time off. Everyone had come down with the same bad cold that I got at the end of the week (which, by the way, was probably the reason I had bad symptoms earlier in the week -- mast cells can become over-reactive when faced with an actual threat like a cold). My director took more than a day off. A few of my other coworkers took a day off. There were moments when I was actually working harder than usual, despite how awful I felt, because there were so few of us left. I thought about taking time off to recover. Yet when I brought it up at work, I felt like I couldn't follow through. I don't know how much was coming from my coworkers and how much was in my own head, but I left each conversation feeling like taking a day off would only make things worse for me and my coworkers, so I continued to push through. It was frustrating, though, to see other people get time off to rest, knowing that my body probably felt significantly worse than theirs.

**Side note: you might be wondering why I might feel sick days are unacceptable "in my own head." I think a variety of insecurities play a role, as well as the fact that I am sick constantly so in order to ever be at work, I need a strong skeptic in my head. But more tangibly, I haven't always been received well in the past. Case in point, my previous supervisor's reaction to me asking if I could have a day off because I was having horrible medication-induced morning sickness was "this can't keep happening, you know." This in the same week that our director took two and a half days off for a cold. The message stuck.

So yeah, it's often frustrating when I'm struggling to make it through something awful and look around and feel that I'm the only one not taking a day off. Part of this, like I said earlier, is because I am always sick, so it's harder to justify when I should be out or not. It's made even more difficult because I'm the only teacher in our program, so if I'm not there, it's really tough for anyone to cover for me. It ends up being more work sometimes to have to coordinate coverage and redo all of my lessons for the rest of the week than to just go in.

The second striking observation happened on the following Monday. I spent the whole weekend sleeping and resting, rather than the fun things I'd planned to do on my first weekend free in forever. When I came in Monday, I was likely not contagious anymore, but my cold was in the stage where it was all trying to get out of my face -- I had a nasty sounding cough, occasional sneezes, and a very snotty nose. Within minutes of arriving to our morning staff meeting, all of my coworkers had reacted in some way, whether with support and concerned "you sound so sick! Are you feeling ok?" or actually encouraging me to take the day off!

I honestly wanted to scream at them all. I felt leagues better than I had for the entire week prior. Yet now they thought I was sick enough to suddenly deserve the day off. The difference in reactions was so massive. I wanted to know why no one had shown that kind of compassion or concern or support the week before. The reason was simple; my symptoms the week before had been invisible. No one could hear or see what was wrong with me. I'm pretty good at smiling through pain, nausea, and fatigue by this point. But with my cold, they could see my bleary, red eyes and raw nose. They could hear my voice drop an octave, could hear me cough.

Maybe it shouldn't matter if people notice. I don't need people doting on me every time I feel bad. The reactions to my cold actually felt quite over-the-top and unnecessary. But it would be really nice once in awhile when I'm experiencing bad, isolating, scary symptoms (like... not a cold), to have someone notice and ask me if I'm ok or if I need anything, or even just to tell me they noticed and that they want to show compassion for me. It would make the constant symptoms more bearable to feel acknowledged and less alone.

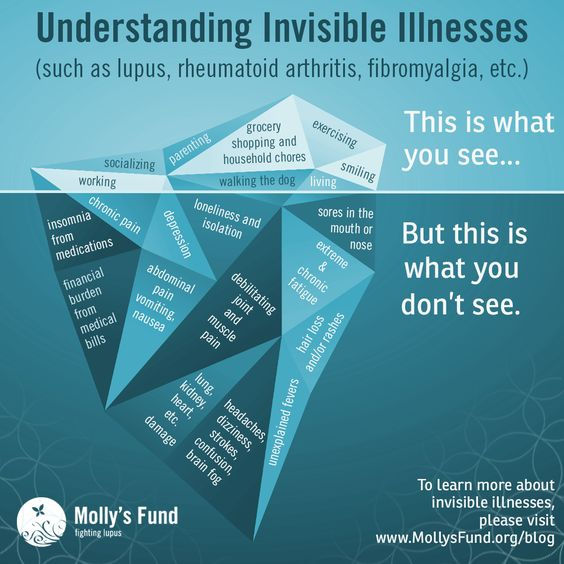

So, when people talk about invisible illness, this is what they mean. To be honest, I'm not always sure the invisibility is worse than a visible chronic illness -- being sick all the time sucks either way, it's just different. If I had a visible illness, sure people would notice more and therefore show more compassion, but they'd eventually grow fatigued from trying to care so often, and my guess is they'd start to avoid me because it's too exhausting to be reminded of someone else's pain, or to have constant reminders of how different they are from you. I would never even have the option of hiding it if the situation required to not be noticed. It is nice sometimes to be able to have an identity other than my illness, and I'm sure it's harder to do that when people are constantly reminded of it, just by looking at you.

What's odd about my situation is that I'm stuck in the middle. It can be visible if I let it show by not covering up my rashy skin, by letting the fatigue or anxiety show, being honest about why I've had to run to the bathroom all morning, or unclenching my muscles to let the twitching consume my body (I actually did that one this week -- let my twitches out because it hurts to hold them in -- and I'm not eager to be looked at that way again). I fight so hard to not let it show. Sometimes the hiding it takes so much effort that I'm too exhausted to do anything else by the time I get home around 1:00. I'm actively making it invisible when I could let some of it show. It doesn't seem professional to be sickly, though, or maybe I'm just scared of people pulling away like they often do when I open up those doors. So I keep it all hidden, despite the huge cost to myself. I'm choosing invisibility and then feeling frustrated when I'm invisible...

I'm still not entirely sure why the invisible piece feels so important, but hopefully you at least get it a little. It's isolating. It makes you feel trapped in your own head. Other people don't bring it up, so you feel odd talking about it. You want people to know how bad it feels, but don't want to sound like a whiner. When the symptoms are stigmatized, not only do you not know when or how often to bring it up, you start to understand that you actually can't talk about it without being judged. So many people treat you like it's all in your head that you start to think you're actually faking it. People look at you funny when you need accommodations. If I had a bad limp or had to use crutches, people wouldn't think twice about letting me sit down when needed or letting me take more time to walk places. But they can't see my joint issues; I look quite healthy, so it doesn't make sense when I need a little extra time or help or supports.

For other people's experiences, here's an awesome compilation of stories/quotes from other people with invisible illnesses. Check it out! It does a great job of showing a range of responses.

If you happen to have people in your life with invisible illnesses (odds are you do), maybe check in with them once in awhile. Ask them how they feel today, and then really genuinely listen. Even just one person acknowledging that they really see you, including what you have to go through every day, can go a long way.

Want to read more? I found this short piece helpful, especially the bit at the end about taking people to the doctor with you. I always want to do that, to have someone professional verify that I am working hard to beat it and that the weird accommodations I ask for are really needed. I tend to go alone, but maybe I should start following that instinct.